Can workers help reform fossil fuel companies?

The need to pressure companies to be more selective about who they work with

Many by now will have seen Al Gore’s latest rousing TED talk on the fossil fuel industry, how it has embedded itself into the annual COP process and is seeking to slow climate action down wherever it can. “The climate crisis is a fossil fuel crisis,” says Gore.

While Gore has long been outspoken about the climate denialism of fossil fuel companies, others had hoped they could play a more constructive role in the green transition. Over the past year though that optimism has faded as many companies have scaled back their climate targets in response to booming oil revenues. “I thought fossil fuel firms could change. I was wrong” was the headline of an opinion piece by Christiana Figueres, a climate negotiator. The Church of England, which held investments in many fossil fuel companies and had been vigorously engaging with them to improve their climate performance, announced it would divest its holdings in response to the lack of progress.

There is an increasing sense then that the industry is unlikely to provide even the mildest supportive tailwinds for the transition. Policy changes and disruptive technologies from newcomers were always going to play a bigger part in the solution than self-directed transformation by fossil fuel incumbents, but it’s increasingly in doubt that the latter will play any part, other than to obstruct.

What does this mean for sustainability-minded workers who want to influence the fossil fuel industry?

Workers influencing the industry from the outside

The most obvious thing that employees outside of the industry can push for is for their employer to switch to 100% renewable energy, reducing the demand for the industry’s products.

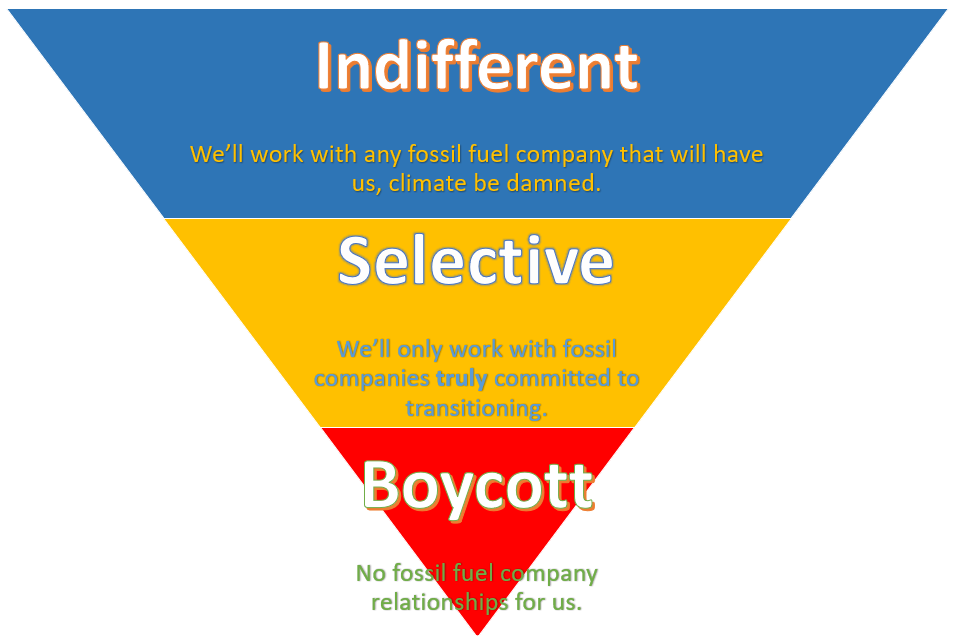

Beyond this though, many companies have other relationships with the industry, as customers or partners. For these companies and their employees, it appears they have three options to guide their work with the industry: boycott, be selective, or be indifferent.

Some employees have pushed for some form of boycott - at tech giant Microsoft, the consultant McKinsey, the PR company Edelman, employees advocated and organised to try to get their companies to drop all fossil fuel clients and stop facilitating their negative impacts on the planet.

The challenge is that for many, the fossil fuel industry is more than a source of energy: it is a source of revenue. It has deep pockets, and service providers are not eager to turn their back on it. And so the frequent line that company executives take in response to employee advocacy is “the industry needs our help. We should work with them to support them in transitioning” (this was the response in all three of the examples mentioned above).

Which sounds sensible, in theory. The issue is that in practice few fossil fuel companies appear genuinely interested in transitioning, and so a blanket agreement to “work with the industry” ends up facilitating continued obstruction and extraction.

Microsoft published energy principles last year that partly emerged out of a dialogue with employees, setting out how it will work with the industry. It contains a stated commitment to selectiveness. For certain specialised services it could provide to fossil fuel companies, it pledged to only provide these to companies with a target of net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

This sounds like being selective, but is actually close enough to indifference. Of the 171 major emitters targeted by investor initiative Climate Action 100+ for engagement, 75% have net zero targets.1 This is not a meaningful signal of an intention to transition. 2050 is a long time away, and many companies have sought to increase their fossil fuel production and exploration to exploit higher oil prices while maintaining their long-term target.

Maybe Microsoft has the right idea, but has chosen a poor metric. Emissions need to be halved by 2030, so we need to focus on shorter-term indicators. Nearer-term targets (emission reductions by 2025 or 2030) and companies’ capital expenditure plans (whether their investment plans are aligned with the Paris agreement’s objectives) show a much more accurate picture of who is actually committed to transitioning.2

Focusing on shorter-term indicators is also more relevant for the work of a service provider - they’re trying to help a company with what it’s trying to accomplish today, not its tentative aspirations 30 years down the line.

The figures for companies with short-term commitments are so low in fact that some might argue that only agreeing to work with such companies comes close to a full industry boycott. But if more consultants, PR companies, banks, insurers and other service providers aligned on a common expectation, it could be more effective than a boycott at pushing those companies to take an achievable step forward.

Disclaimer: I am employed by the Principles for Responsible Investment, one of the groups which helps coordinate Climate Action 100+.