A brief history of employee activism

Workers have been caring about more than their own welfare for a long time

New year, samesletter.

The idea for Honest Work first came to me in 2019, inspired in no small part by a wave of employee activism then taking place, particularly in the US tech industry. Workers were defying the common idea that they care only about good working conditions, and were challenging their companies’ work with US immigration services, their political donations, their contributions to online misinformation and censorship. Of all the campaigns, perhaps the most successful were those focused on climate change: workers at Microsoft, Alphabet and Amazon sent letters, joined the climate strikes and (at Amazon) even filed a shareholder proposal. All three companies subsequently made commitments to achieve net zero emissions, with Microsoft going as far as to pledge net negative emissions by 2030.

Despite recent layoffs, workers at big tech companies are among the most privileged in the world, with high salaries, amazing perks and a long list of job opportunities available to them if their current employment relationship comes to an end. As such, it is tempting to view such workplace advocacy as the exclusive domain of those with comfy jobs and their material needs taken care of. It’s all very well for them…

Such a view is not baseless; raising significant challenges to the impact an employer is having on the world may be too risky for many. Yet the employee activism we’ve been seeing on non-workplace issues is just the latest in a long history of workers standing up for what they believe in. Often, the risks have been high.1

1862: The British working class against American slavery

The earliest example I have found of “employee activism” for the common good is a powerful one.2 During the American Civil War, Abraham Lincoln’s forces blockaded the southern states from exporting their slave-picked cotton, which was the source of the vast majority of cotton for the mills of Lancashire in the UK. Without it, mills were closed and thousands of workers faced unemployment, starvation and destitution.

Shipping companies and mill owners were clamouring for the UK’s Royal Navy to smash Lincoln’s blockade and enable the Confederacy to export. Workers and trade unions, however, held a number of meetings to support the northern states and the blockade. On New Year’s Eve of 1862, a meeting of cotton workers and others in Manchester passed a motion in support of the blockade and the fight for the abolition of slavery – despite the immense hardship it was causing them.

Liberal MP John Bright told a mass meeting of trade unionists:

"I have faith in you. Impartial history will tell that, when your statesmen were hostile or coldly neutral, when many of your rich men were corrupt, when your press - which ought to have instructed and defended - was mainly written to betray, the fate of a Continent and of its vast population being in peril, you clung to freedom."

1930s: Dockworkers against fascism

Before the commencement of World War II in 1939 the Axis powers of Germany, Italy and Japan had already invaded multiple countries and committed numerous atrocities. Workers in other countries at times refused to engage in labour that could in any way support the Axis’ aggression.

In the aftermath of the Nanjing Massacre, a mass murder of Chinese civilians by Japanese forces, the Australian Council of Trade Unions called for an embargo on the export of iron to Japan. This led to workers at ports around Australia refusing to load any ships bound for Japan, and culminated in the Dalfram dispute, where workers in New South Wales walked off the job and went on strike for over 10 weeks, refusing to load a ship with pig iron for Japan. In South Africa, workers refused to load meat on a ship destined for the Italian army that had recently invaded Ethiopia.

Dockworkers around the world continue to engage in such acts of international solidarity, more recently refusing to unload Israeli goods following a bombardment of Palestine, and arms destined for Zimbabwe following a bout of state-sponsored violence.

1970s: Australia’s green bans

In the late 1960s Australia saw a wave of development, which led to concerns among communities that their local area and environment would be damaged. Concerned communities brought their concerns to trade unions in the construction industry, who often stood in solidarity with residents and began to refuse construction projects, on the basis that “workers have a right to insist their labour not be used in harmful ways”.

The decade saw union workers institute a number of “green bans”, refusing building projects that would reduce accessibility to green spaces for working people, or otherwise damage neighbourhoods. When a company seeking to erect a luxury housing development threatened to use non-union labour, workers on a separate project for the company threatened to abandon that development too if they did so, and the company relented.

Secretary of the Builders Labourers Federation Jack Mundey askd:

“What is the use of higher wages alone, if we have to live in cities devoid of parks, bare of trees, in an atmosphere poisoned by pollution and vibrating with the noise of hundreds of thousands of units of private transport?”

There was even a “pink ban”, with union workers refusing to do further building work for Macquarie University after they expelled a student for being gay.

1960s to 80s: Boycotting apartheid South Africa

The treatment of black people in South Africa mobilised workers from various industries around the world to challenge the role their companies were playing in enabling that racist regime.

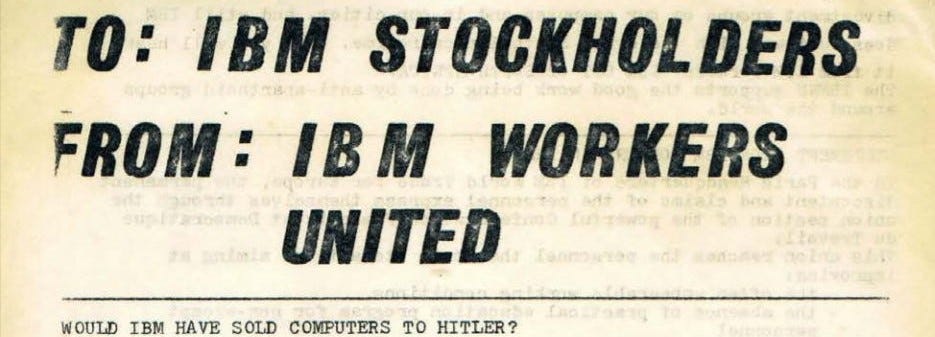

Workers at Polaroid and IBM protested their employers’ work with the South African government, and circulated flyers to coworkers and shareholders. On multiple occasions dockworkers refused to unload ships containing South African cargo. And in my native Ireland, a staff member at retailer Dunnes Stores was suspended for following a union instruction not to handle goods from apartheid South Africa. This led to 12 young workers going on a strike that would last for 3 years.

2010s and 2020s: Across locations, industries, issues

While it may be partly because of information being more readily available, employee activism on ethical, non-workplace issues appears to have become much more widespread in recent years.

2018 and 2019 saw the biggest jumps in such incidents, mainly driven by efforts by tech workers seeking to prevent their employers from working with the US military and immigration agencies. But the industries where this has been happening and the issues at stake have only grown. Workers have pushed their companies to have more positive racial impacts following the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020. Insurance workers, yoga clothing ambassadors, consultants and PR professionals have been pressuring their employers to do better on their unique contributions to the climate crisis. Workers have been holding internal debates, writing petitions, posting on social media and even creating websites in their efforts to push for change.

Some takeaways

What does this rapid history lesson tell us?

Employees have sometimes stood alone for what was right. At several important historical moments, business owners were happy to profit from situations we would now consider morally repugnant. It was employees who were led by their conscience, and fought to do the right thing.

Employee activism doesn’t have to be the domain of the privileged. Blue-collar workers have been in the vanguard of activism on ethical issues. While it’s natural that wealthier, more secure workers are prepared to take bigger risks, all can contribute in some way to building better companies.

Unions have often been indispensable in building solidarity between communities. Today, trade/labour unions’ membership has shrunk, and they rarely include “ethical” concerns like climate change in negotiations with companies. We need more unions taking these issues more seriously3, and to support other forms of worker organising to enable them to advocate on these non-traditional issues that they nonetheless care about.

Next steps

When we hear about people in the past standing up for what is right, there can be a tendency to assume we would have done the same. That we would have recognised these historical injustices for what they were, despite the fact that at the time they were widely accepted as inevitable and the way things were. That we would have raised our head above the parapet despite the risks, the discomfort, the social shunning that we would face.

I think we overestimate ourselves. There are many things that we widely tolerate today that future generations may judge as horrific as we view the likes of slavery and apartheid today. Supply chains with awful working conditions to allow us to buy cheaper clothes. The treatment of animals in factory farms. Individually and collectively continuing to emit high levels of carbon knowing that it will be the poor who pay. We may dislike these things, but our inaction allows them to continue.

ACTION: Consider what your own ethical “red lines” might be. What problems, local or global, do you want to avoid contributing to at all costs? Write them down, and make a commitment to yourself to tackle them wherever they intersect with your life - as employee, consumer, citizen. Do a bit of digging to see if they do in fact touch your life somehow, especially in the workplace. Is there something you can do about it?

Finally… Last month in employee activism:

Employees at Neuralink, the medical device company owned by Elon Musk, have been lodging internal complaints about the company’s approach to animal testing, arguing that Musk’s demands to speed up research have led to many more animals being killed after experiments than would otherwise be the case.

Though I have been trying to research this history over the last few years, I’m not a historian. If you find inaccuracies or omissions or have other recommendations, please drop me a line!

Of course, it could be – and was – argued that slave labour constitutes an existential threat to free labour everywhere, and there is some element of self-interest in waged workers opposing it. Perhaps, as philosopher Joey Tribbiani has argued, few acts can ever be entirely selfless.

A good example of what this could look like is the Bargaining for the Common Good movement in the US.